Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

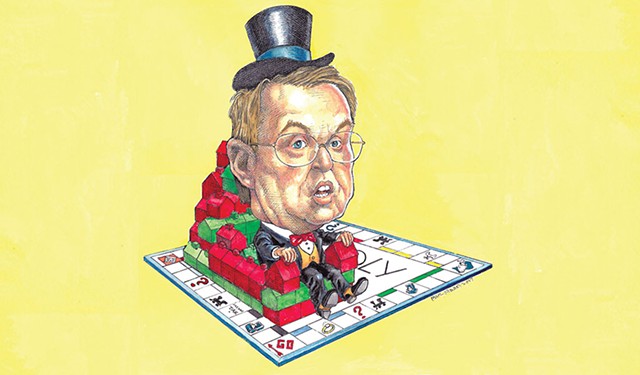

Thom Lauzon Is Barre's Mayor — and Its Biggest Developer. Is That a Problem?

Published September 6, 2017 at 10:00 a.m.

Barre Mayor Thom Lauzon steered his BMW behind a vacant store on North Main Street, then hopped out and grumbled: "I hate empty buildings. I'd rather let people use them for free than have them empty."

He parked at the loading dock — an unusual place to start a tour with a reporter on an August afternoon — and surveyed the bleak surroundings on the backside of the Granite City's downtown strip. Before him was an abandoned structure known to locals as the Homer Fitts building. To his right was Downtown Rentals, which brokers cheap rooms. To his left, another empty edifice, and next to that, a 100-year-old, largely vacant brick building. At the southern end of the dilapidated block is where Vermont's sole strip club, Planet Rock, and an erotic bookstore and head shop operate, to the chagrin of many in this historically Catholic municipality.

If Lauzon gets his wish, all of this real estate will be renovated or removed to make way for a $30 million project dubbed the Park Center, a development of condos, high-end apartments, a grocery store, and a convention center and hotel.

"This could transform Barre," he said of what would be the city's largest development in recent history.

But Lauzon is not boosting this project on behalf of some developer; Park Center is his, and the volunteer mayor stands to make millions if he can convince local and state regulators to green-light it.

The project could be the crown jewel in Lauzon's real estate empire — or a conflict of interest so glaring that it puts an end to the way he's been doing business in Barre.

In the past 10 years, Lauzon has taken control of Barre's government and simultaneously become its most prominent developer.

Lauzon and his allies have long controlled a majority on the city council, which appoints members of the Development Review Board and other local commissions. Barre's paid city manager, nominally in charge of day-to-day municipal functions, is a longtime friend who credits Lauzon with persuading him to take the job.

Lauzon is even the landlord for his community's newspaper, the Barre-Montpelier Times Argus. No one has bothered to run against him in his last five reelection bids.

Meanwhile, Lauzon has become the largest individual property owner in Barre. He and his wife, Karen, own dozens of properties, many of them downtown, with a combined assessed value of $8.7 million — 1.8 percent of the city's grand list. The Lauzons rent space to Aubuchon Hardware and Dollar General stores, a trendy restaurant, a gym, offices, small industrial companies, and more than a dozen apartments. Lauzon also owns numerous vacant lots and storefronts sprinkled throughout the city.

His dual, arguably incompatible, roles were on display in June, when Lauzon strong-armed the city council to go into executive session — possibly in violation of the state's open meeting law — to hear about his previously secret plans for Park Center. The public and press were kept out, and, in a subsequent VTDigger.org story, Barre City Councilor Sue Higby criticized the way Lauzon handled the situation.

"For me and many others, the key concern has been about transparency and what is very clearly a conflict of interest," her colleague, Councilor Brandon Batham, told Seven Days. "It's not an appropriate thing for him to do while he is mayor of Barre. It's not about Thom Lauzon. It's about public trust."

While the Park Center proposal has prompted ethical questions about Lauzon's conduct, records show that his potential conflicts are not new. In the past several years, the moderate Republican, who has expressed some interest in seeking higher office, has frequently gone before not just the city council but also the Planning Commission, the Development Review Board and the Board of Civil Authority as a private developer.

He has asked for curb cuts, permission to knock down buildings and lower tax assessments. He has also scored at least $900,000 in grants and tax credits from the state and federal governments and successfully lobbied Vermont for money to improve sidewalks and other downtown infrastructure alongside property he owns.

Lauzon dismisses his critics, calling them "background noise" and "yipper dogs nipping at your heels." And he argues that what's good for him is also good for Barre. The city of 9,000 has long been economically depressed, and Lauzon's projects — specifically the renovation of the three-story Aldrich Block that hosts the popular Cornerstone Pub & Kitchen and the mixed-use City Place building — have made the downtown a livelier place than it was before he took office.

"If you have a concern about it, throw your hat in the ring, grow some balls and try to do something," Lauzon said. "I haven't failed Barre yet. I know how to get things done. No one else is turning over stones in Barre, trying to find projects. Am I the guy you want to cuddle with? No. That's not who I am. But if you're going out to play and you're picking a team to win, you're picking me."

Man About Town

Lauzon, 56, looks like a CPA, and he is one. A bespectacled man of average height with a full head of neatly combed brown hair, he owns the local accounting firm that once employed him. His most distinctive physical characteristic is a ready-for-radio voice, which sounds a bit like Alan Alda's.

He likes the sound of it, too, whether he's talking about "making his first million" or how little sleep he requires: four hours a night.

Although his last name is French Canadian, there's a touch of The Godfather in Lauzon, who moved from New Jersey to Vermont as a boy and has spent most of his life in Barre.

For example, he keeps alive a rumor, which is prevalent in Barre, that he torched the Aldrich Block in 2010 and funded its renovations with the insurance settlement — even though police proved that two teenagers were responsible. With this reporter in tow, Lauzon joked about the other buildings he'd "burned down."

He also made it clear that he knew whom I was talking to and what I was asking them. "It must be frustrating to go through all that paperwork and not find anything because there's nothing there," he said in a phone call that came out of the blue on a weekend. The message was: You can't make a move without me finding out about it.

Lauzon knows all about Barre, too, and is a walking, talking encyclopedia of the city's challenges. Off the top of his head, he rattled off the amount of money the city generates in parking fees, the number of probationers living in town and Barre's average home sale price.

That last figure has gone up since the Lauzon family moved from Middletown, N.J., to Barre in 1963, when his father, who worked for IBM, took a job setting up an IT system for the State of Vermont. Their home on Washington Street was within biking distance of future governor Phil Scott's. The two men knew each other — and Lauzon describes himself as a "Phil Scott Republican" — but Lauzon said he was actually closer to Scott's younger brother Chuck.

After graduating from Spaulding High School, Lauzon went to Saint Michael's College, where he studied accounting, and then took a job on Wall Street. On a visit back to Barre to see his parents, he went out for a drink at a local dive bar, the long-defunct Bullwinkle's. He saw Karen Champy, a local girl three years his junior, and asked her to dance.

Their first date, a couple of days later, lasted for 12 hours and ended with a visit to meet his ailing grandfather.

Smitten, Lauzon moved home and took an accounting job at Salvador and Babic, which is now his company. To make extra money, he and Karen bought a house in town and fixed it up to rent. Their plan was to sell it once their son Alex, then 3, was 18, to fund his college tuition. Instead they bought another property. And another.

Karen eventually quit her job as a pension services representative at National Life Group to manage the couple's growing real estate portfolio. Daughter Miranda was born in 1993.

Through two dozen registered companies, the Lauzons now own 54 properties in Barre, according to city and state records, including a fire-damaged former bed-and-breakfast on Route 14. In addition, they have a commercial building in Berlin and a Burlington condo.

Lauzon bought most of the properties at foreclosure auctions. One exception, the Victorian B&B, was obtained in a private transaction negotiated before it went on the market. Lauzon said he convinced the former owners to let it go for $85,000 so he and Karen could bring it back to life.

Barre Mayor Thom Lauzon's City Properties

Barre records list these properties as registered to Lauzon or one of his LLCs.

- Andrea Suozzo

- Source: Vermont Secretary of State Business Registry; Barre City Grand List

Unlike some developers, Lauzon said he has little interest in architecture or design — he leaves that stuff to Karen. He makes an effort to portray her as an equal partner, much the way U.S. Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) incessantly invokes his wife — "Marcelle and I..." — at every opportunity.

One big difference: Last year Karen ran for a seat in the legislature against two incumbents representing Barre City and was handily defeated.

To Lauzon, buildings are investments. And he has one rule, above all others, when deciding whether to purchase a property: Buy low.

"In real estate, the only mistake you can't recover from is paying too much," Lauzon said.

But it's about more than money, Karen said, explaining what motivated the couple to stay in Barre.

Lauzon's first high-profile project was the renovation of the historic Aldrich Block building, which had sat vacant for years. He struck a deal with two restaurateurs, who opened Cornerstone Pub & Kitchen on the first floor in 2013. He rents the second floor to the Times-Argus, as well as two apartments for more than $1,000 a month on the third floor.

"It's not always what we're getting back monetarily. It's saving buildings; it's being proud of what we do," Karen said.

Even his opponents begrudgingly acknowledge that Lauzon is a skilled multitasker who's been successful in most of his endeavors.

"If he has an eye on achieving something, he's going to do it or break a leg trying," former Barre mayor Peter Anthony said of the man who beat him. "I'm very impressed at his achievements."

Power Player

click to enlarge

- Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

- Barre Mayor Thom Lauzon meeting with housing officials and Barre residents in 2013

Barre has a "weak mayor" form of government. A full-time, professional city manager is supposed to run the show.

Lauzon's part-time electoral job comes with a $1,500 stipend — that Lauzon doesn't take — but no office or phone. The only power is in presiding over city council meetings — making him essentially a first among equals on the council — and acting as a city spokesman at ribbon cuttings and minor ceremonies.

Lauzon joked that "nobody told him" he was meant to be a symbolic figurehead. "It's what you make of it," he said of the job. "I don't know any other way to do things."

Despite the lack of formal responsibilities, Lauzon has become deeply involved in Barre's day-to-day affairs. He takes phone calls from people looking to do business in the city and arranges and attends meetings with state officials, financiers and businesspeople. When a high-risk sex offender recently moved to town, it was Lauzon who coordinated the response with local police and the Department of Corrections. The mayor has even been known to show up at fires in the middle of the night to offer support to victims.

One rainy day in July, he was scheduled to throw out the first pitch at that night's Vermont Mountaineers baseball game. But it was pouring outside. Surely the game would be canceled, I suggested. Lauzon paused, then looked me in the eye.

"I'm not a pussy," he said sternly. "We're not pussies here." He dutifully carried out his obligation, but the game later did get rained out.

Among Lauzon's admirers is former Rutland mayor Chris Louras, who, as a full-time "strong mayor," ran city hall, oversaw more than 100 employees and devoted all his working hours to municipal matters. Through the force of his charismatic personality, Lauzon has achieved similar influence in Barre, Louras said.

"It's through sheer will and the fact that, in my opinion, he's very successful at getting things done for his community," Louras said. "Thom is just a persistent dude, and his personality fits his leadership style, so Barre appears to have a strong-mayor government."

Louras, who lost his reelection bid in March, dismissed concerns about Lauzon's various conflicts, saying that as long as he didn't conceal his involvements, he was doing nothing wrong.

City Manager Steve Mackenzie, who served on the council with Lauzon, seconded that. "What's your point? What's the issue?" Mackenzie said. "He's a dynamic and visionary individual. He seems to have the energy of any 10 people I know. And he's got to be the most networked guy I've seen in my life. I don't see where Thom has abused the relationship. To whatever extent he has benefited personally, the city has benefited as well."

Records show the Lauzons have made at least a dozen appearances in the past six years before various Barre boards and commissions, many of whose members the mayor had a hand in appointing.

For example, in 2014, Lauzon got permission from the Development Review Board to demolish a building he owns on Washington Street. He did the same thing in 2012 with a home on Elm Street. This year, the DRB approved his request to move the curb cut on a commercial parcel he owns on Elm.

Lauzon sits on the Board of Civil Authority, which decides tax assessment appeals on residential and commercial properties in Barre. Records show he has recused himself on votes regarding properties he owns, but not those involving the homes and businesses of others.

The board doesn't always give Lauzon what he wants: In 2014, it denied his request to lower assessments on two of his properties — one vacant, the other a parking lot.

In June, Lauzon protested the Barre tax assessor's decision to dramatically increase the value of a commercial building he owns; a recent addition had motivated the assessor to bump it from $485,000 to $995,000. Lauzon complained to the assessor that the change in size was overstated — in the end, the assessor signed off on $786,000, and Lauzon never appealed the decision to the BCA.

The same month, Lauzon went before the Planning Commission, which is rewriting Barre's zoning regulations, to suggest that it allow for more dense development on some residential parcels. Lauzon told the members that he is considering building a cluster of tiny houses on at least one of his properties.

"It always does seem when he comes either before the city council or Planning Commission and is talking about a project, his land is involved, too," Planning Commission chair Jackie Calder said. "I don't think he has any more influence than anyone else, but he's always there; he always has a voice. Sometimes he makes a good point."

Lauzon said his self-interest isn't problematic because he has never hidden it. When he first ran for mayor in 2006 and unseated Anthony in a landslide, Lauzon was already a developer and property owner.

"Would you want a mayor who doesn't want to invest in the community?" Lauzon asked.

Lauzon leases space to the Times-Argus — he bought the paper's old building, along the Winooski River just outside downtown, in 2013.

Times-Argus editor Steve Pappas said the paper has not changed the way it writes about Lauzon because he's the landlord.

"We made a decision very early that we could not let that interfere with our coverage of him," Pappas said, noting that the paper has published numerous critical editorials about Lauzon. "He has so many things going on in the community that we couldn't hold back at all."

Even if it were possible to avoid Lauzon, Pappas said, it would be bad for business.

"We sell more papers and get more hits when Thom Lauzon mouths off," Pappas said. "People either hate Thom or they are grateful for him. He's a conundrum."

Rebuilding Barre

Barre was once the Winooski of Vermont. When demand for its granite was at its peak and the quarries were operating at full capacity, it was the most diverse city in the state. Barre has since struggled to maintain population and stay economically vital, while neighboring Montpelier has fared better. State government has turned out to be a more reliable source of employment.

Downtown Barre is still pockmarked with empty storefronts years after a "renaissance" that didn't fully deliver. The Washington County criminal courthouse and a few state government office buildings account for much of the downtown's daytime traffic.

Lauzon wants to change that. He has quietly spent much of the past year laying the groundwork for the Park Center project, which would revitalize a moribund block hemmed in by North Main Street, Keith Avenue and Summer Street. Some existing buildings would be knocked down, and others refurbished.

The backbone of the project, Lauzon insisted, is housing.

It calls for 30 upscale apartments — the kind that would go for more than $2,000 a month in Burlington but around $1,200 in Barre — along with a dozen condos. He hopes to draw young professionals working at Blue Cross Blue Shield of Vermont in Berlin and National Life Group in Montpelier who want to live in a walkable downtown.

"If you want to rebuild a downtown today, you don't start with retail," Lauzon said. "You start with housing."

The building Lauzon owns, the former home of the Homer Fitts department store, would be knocked down to make way for a five-story hotel and convention center.

Lauzon said he has secured an option to buy the Worthen Block, on North Main Street, along with another vacant building, that would be the site of the housing.

It is hard to find anyone in Barre who thinks the project itself is a bad idea. Even Lauzon's detractors on the city council like it.

"I'm excited that Thom Lauzon, the private developer, is pursuing that," Batham said. "He has a track record of success."

But the way Lauzon unveiled his plans raised ethical concerns. He informed the council that he wanted to make a presentation — but on his terms, behind closed doors.

Lauzon told its members they could not take notes or discuss what they learned.

"I hope you understand that, and, if you don't, you have to leave," Lauzon said, according to VTDigger.org.

The council then voted on whether or not to go into executive session. Lauzon did not recuse himself — in fact, he led the meeting. The council voted 4-1, with Batham abstaining, to retreat behind closed doors.

The dissenting vote came from Councilor Higby, who pushed back against the plan for a closed-door discussion when Lauzon notified the council of it days prior to the meeting.

"He called me and told me he was going to go ahead and that I didn't know anything about real estate development," Higby said. "It was a huge mistake. Yes, he did violate the public meeting law. And if you have to go into executive session to prevent the public from knowing what the project is, it shows weak leadership. You're showing your project isn't strong enough to stand on its own."

Lauzon's secret session consisted of a 90-minute PowerPoint presentation to the council and a handpicked crowd of about a dozen people, including two state commissioners. Lauzon argued that it was proper because he was merely giving a background briefing and was not — at least not yet — asking councilors for anything.

Why do it at all?

Lauzon said he didn't want to tip his hand to property owners who might hold out for a higher price if they knew that developers had big dreams for their land.

"If you want a project to flop, let the world know what you're doing before you have all the moving parts," he said.

There is no law or regulation on the books that prevents Lauzon from playing dual roles as developer and mayor, Secretary of State Jim Condos said.

Condos referred Seven Days to Barre's conflict-of-interest policy. Enacted in 2009, it calls for officials to disclose their potential conflicts and act "fairly, objectively and in the public interest."

"Most of the policies leave it up to the individuals to decide whether they have a conflict or not," Condos said, declining to discuss Lauzon in detail. "It's not up to the boards to decide. I know Thom is one of the biggest landowners in town, and, depending on how it's handled, it could seem to be a problem, but I don't know if it is."

In interviews, Lauzon said he has not violated Barre's policy. He explained his actions this way: The year of planning, buying options on properties, studying economics and drawing up plans for the project was the work of Thom Lauzon, private citizen. The act of calling for an executive session was the work of Thom Lauzon, public official.

Days after the executive session, Lauzon briefly changed his mind about that.

He announced that he would back away from the project and proposed a far-fetched idea: that the city should appoint a 10-member development team to lead the effort.

Lauzon was no doubt recalling what happened with City Place, his last development of this scale, in 2014.

Then, as now, Lauzon secured options to buy properties on a listless block of North Main Street in the heart of Barre and dreamed of creating a mixed-use project to revitalize it.

He wooed former governor Peter Shumlin and other state leaders to secure two key tenants — the Agency of Education and the Agency of Human Services — to make City Place financially viable.

That was a conflict of interest, and Lauzon realized it.

"I fully recognized that I needed to hand that project off," he said. "I can't profit from it, can't be an owner while I'm sitting in the governor's office saying, 'Will you sign a multiyear lease and promote our downtown?'"

He transferred his options to the city, without being compensated, but as mayor worked to see the project through.

In the end, Lauzon said his critics "were very comfortable with my intentions and my integrity and how I got things done. City Place worked."

In addition to the state offices that bring workers — and lunch customers — to Barre, the building now hosts a Positive Pie pizzeria and an office for Edward Jones Investments.

Recuse me

Lauzon could have gone the same route with Park Center. But within days of the executive session, he had changed his mind again. Instead of divesting, as he did with City Place, he hired Brattleboro's M&S Development to help shepherd the project. The company provides professional expertise — and political cover — for the mayor.

The firm's president, Bob Stevens, hopes to have plans for Park Center wrapped up, and tenants secured, within six months.

In an interview, Stevens said the project would need lots of help from the government — state and local. Developers will seek tax credits, especially the New Markets Tax Credit, which provides aid to projects that create jobs in struggling downtowns. City Place received $10 million through the program.

"If we don't get that, we don't do that project," Stevens said.

M&S will likely hit up Barre City Hall for support, too, Stevens said.

The hope is to use Barre's Tax Increment Financing District funding to get the city to build a parking garage to support the development.

TIF districts are used to stimulate private investment by financing public infrastructure projects. Cities take out bonds to pay for infrastructure, which theoretically increases property values throughout the district. The taxes generated by those upgrades go toward paying off the bonds.

Such financing would have to be approved by the city council.

"We would work with the city," Stevens said. "We think it needs a parking garage, and we think the parking garage should be a municipal function."

The potential for conflict is clear. Plus, Lauzon lobbied hard to get Barre to create the TIF district, which was formalized in 2013. Did he have any idea then how useful it could be to him?

Lauzon didn't have this project in mind when he pushed for it, he said. If Park Center applies for TIF funding, Lauzon vowed that he would recuse himself from the council's vote.

Meanwhile, councilors should help or get out of the way, according to Lauzon. "The city has nothing in the queue. Thom has something he would like to advance," the mayor said, speaking about himself in the third person. "I don't see how that hurts the council."

Lauzon has options. He likes to tell people that he is rich enough, and close enough to retirement age, to walk away from his responsibilities whenever he wants.

He's been mentioned as a possible candidate for lieutenant governor in 2018 — largely because he hasn't said anything to stop the speculation. He's also suggested that he might step aside as mayor when his term ends next year.

In late August, Lauzon attended a gubernatorial press conference that was held along a brook in Barre that had flooded two years prior. The goal was to tout the rebuilding effort and the state's efforts to prevent future disaster. When he took the podium, Lauzon stayed on message about his community's resiliency.

In later exchanges with reporters, however, the mayor discussed his own future. He wondered aloud if a run for statewide office would be compatible with his temperament.

"Phil Scott is one of the nicest, hardest-working people I know, and I look at the shit he goes through and he lets roll off his back, and I'm not like that," Lauzon told reporters. "That's one of my concerns. How would I respond? In the Facebook era, when people are constantly needling — that's what I think about."

After the August press conference concluded and Scott's entourage trickled out, Lauzon was back in mayoral mode, lecturing about the opiate crisis, low-income housing, his enemies on the city council and, inevitably, plans for his properties.

He was heading back to his BMW when he stopped and said: "Twenty years ago, I never would have believed it if you told me my life would be this bitchin'."

Correction, September 7, 2017: Vermont Rural Ventures administers the New Markets Tax Credit program in the Green Mountain State. A previous version of this story contained an error.

The original print version of this article was headlined "Playing to Win"

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

More By This Author

Speaking of...

-

Barre to Sell Two Parking Lots for $1 to Housing Developer

Apr 22, 2024 -

At Studio Place Arts in Barre, a Group Exhibit Highlights Embroidery

Apr 10, 2024 -

Backstory: July Flood Hit 'Closest to Home' for Barre-Raised Reporter Courtney Lamdin

Dec 27, 2023 -

Volunteers Create Quilts for Residents at Barre-Area Homeless Shelters

Nov 1, 2023 -

Elinor Randall’s Prints Leave ‘Deep Impressions’ at Studio Place Arts

Sep 20, 2023 - More »

Comments (8)

Showing 1-8 of 8

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. Barre to Sell Two Parking Lots for $1 to Housing Developer Housing Crisis

- 2. Vermont Awarded $62 Million in Federal Solar Incentives News

- 3. Vermont Reports Its First Case of the Measles Since 2018 News

- 4. Ed Secretary Saunders Fields Questions at Confirmation Hearing Education

- 5. Home Is Where the Target Is: Suburban SoBu Builds a Downtown Neighborhood Real Estate

- 6. Property Tax Relief Bill Sparks Partisan Feud News

- 7. More Vermont Seniors Are Working, Due to Financial Need or Choice. They May Help Plug the Labor Gap. This Old State

- 1. Totally Transfixed: A Rare Eclipse on a Bluebird Day Dazzled Crowds in Northern Vermont 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 2. Zoie Saunders, Gov. Scott’s Pick for Education Secretary, Faces Questions About Her Qualifications Education

- 3. Don't Trash Those Solar Eclipse Glasses! Groups Collect Them to Be Reused 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 4. Burlington City Council Approves Rezoning Plan to Boost Housing Supply News

- 5. State Will Build Secure Juvenile Treatment Center in Vergennes News

- 6. Rising Costs and Property Tax Hikes Again Threaten the Survival of Small Schools Education

- 7. Queen of the City: Mulvaney-Stanak Sworn In as Burlington Mayor News